Damien Chazelle’s ‘First Man’ documents the life of astronaut Neil Armstrong — the first man to step foot on the moon. The movie opens with Armstrong (Ryan Gosling) bouncing off the atmosphere in an X-15 (a record-setting flight), and through tonal elements of the camera and sound design, we are immersed in Armstrong’s personal experience of the moment. The movie continues this way, whether those moments deal with family, friends, loss, or space flight.

Chazelle’s two previous films are ‘Whiplash’ and ‘La La Land.’ These films, marked by their use of music and precise editing mixed with personal emotions, rightly gained Chazelle recognition as a talented young filmmaker (not to mention a number of Oscars). While ‘First Man’’s reviews have been generally positive, some have noted that this film plays as less personal for Chazelle than his two previous works. While the story itself may not be personal for Chazelle’s own life, it is clearly deeply personal for the main character. Chazelle tactfully combines Armstrong’s inner life and universal humanity with the breadth of his grand achievements. This romance is done brilliantly, and is perhaps the film’s greatest feat.

This choice of story can play somewhat paradoxically — scenes in Armstrong’s kitchen are matched in importance to scenes in space. This juxtaposition, though, is precisely the point. Our individual humanity, drives, and emotions — combined across the billions that make humankind — are what enable our technological, scientific, and cultural progress. Without our inner life, we would be nothing. In order to appreciate and even comprehend the achievement of Armstrong, we have to know the individual. Our knowledge of Neil as a man brings the story down to earth. It inspires us. It makes us believe that a single individual — like us with fears, loss, love, and life — can achieve something extraordinary. The individual is the human story, compounded over generations and civilizations.

Chazelle, cinematographer Linus Sandgren, and others achieved this thesis through technique. A mix of 16mm, 35mm, and IMAX 70mm film fill the movie with the grain, tactile nature, period elements, and resolution of celluloid. Much of the film, particularly scenes on earth and those in the various cockpits, is shot handheld. As Chazelle explains to the American Cinematographer,

“What really attracted me was the ‘mission movie’ aspect and the [opportunity to] strip away the mythology to tell a very-you-are-there ‘documentary’ from the point of view of the person who actually experienced it.”

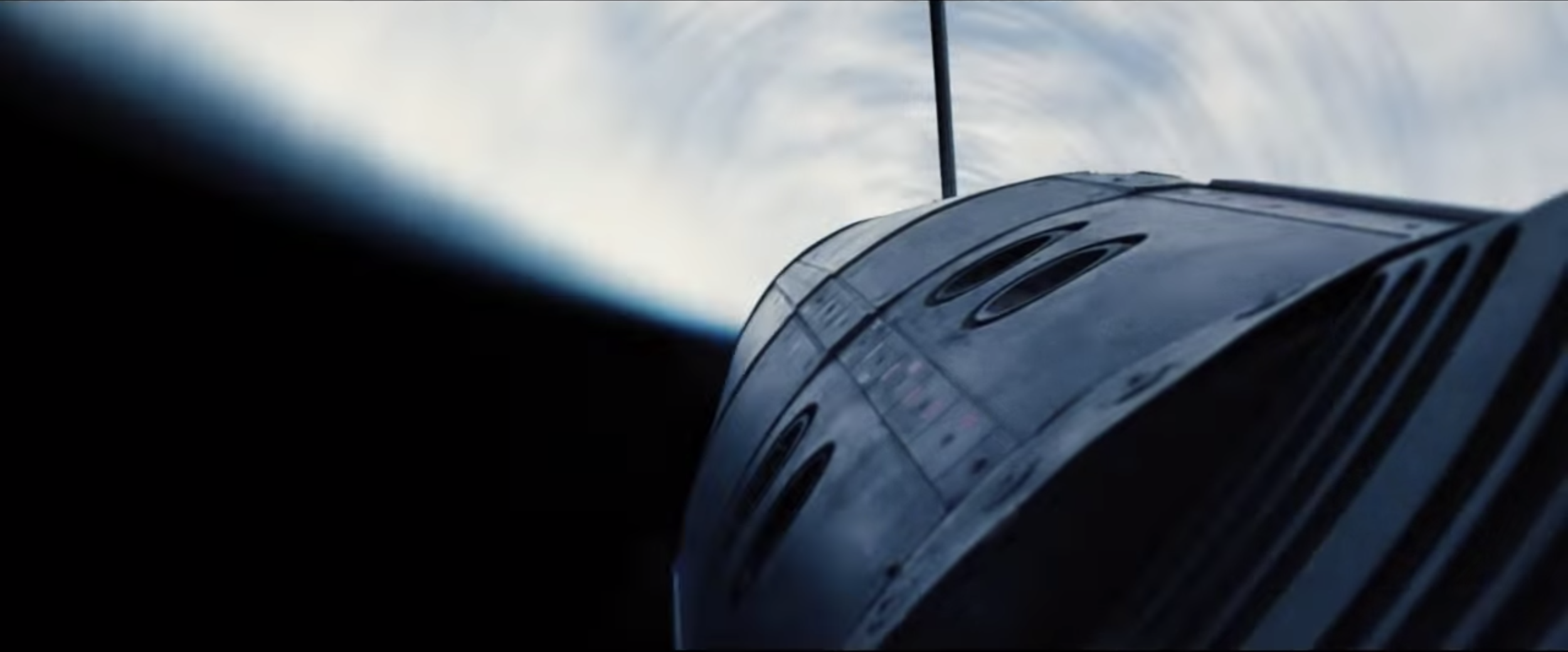

A view from above.

You would initially think a space films means big, wide shots (there are, of course, a few at the right moment), but most of this film takes place very close to the characters. Much of the sets and ships are miniatures, and — similar to Interstellar — we experience the details as the camera rests on the bank of a wing, shows the reflections on the visor of an astronaut’s helmet, or sits adjacent to a measurements on a gauge.

The characteristics of earth and space feel somewhat shared, and an underlying element of spatial emptiness is subtly present throughout the film. As Sandgren explains in the same interview,

“One theme was to work with black negative space in the environments [used for] the drama on Earth, as a metaphor for death and as a foreboding for traveling into the blackness of space.”

This aspect is a bit heavy, but the feeling brought by the very sad loss Armstrong’s family suffers early in the film can be akin to that of floating through space slowly, inching away from what is tangible.

‘First Man’ is a truly cinematic experience, and I’d recommend seeing it in IMAX. Employing a personal character’s odyssey to show universal truths, the film will leave you a bit inspired and with a rounded view of the human experience. Armstrong faced the inner turmoils inherent in that experience, turmoils we all face. He overcame them and walked on the moon, thus making ‘First Man’ — a story of the human spirit — a story worth telling.

- JG

Image via Filmmaker Magazine.