This post is the subject of our second episode with Zero Point Fiction podcast (learn more about our collaboration here). Check out the episode on iTunes and Spotify, or stream it here.

Modern life can sometimes leave us feeling empty. We have access to material standards prior generations could only imagine. Many, particularly the upper middle classes and well-off in the West, are lucky to have optionality, time, and a host of meanings to chose from. Yet meaning can often allude. Modern life can present a mundane quality, and freedom can unintentionally lead to uniformity and indifference.

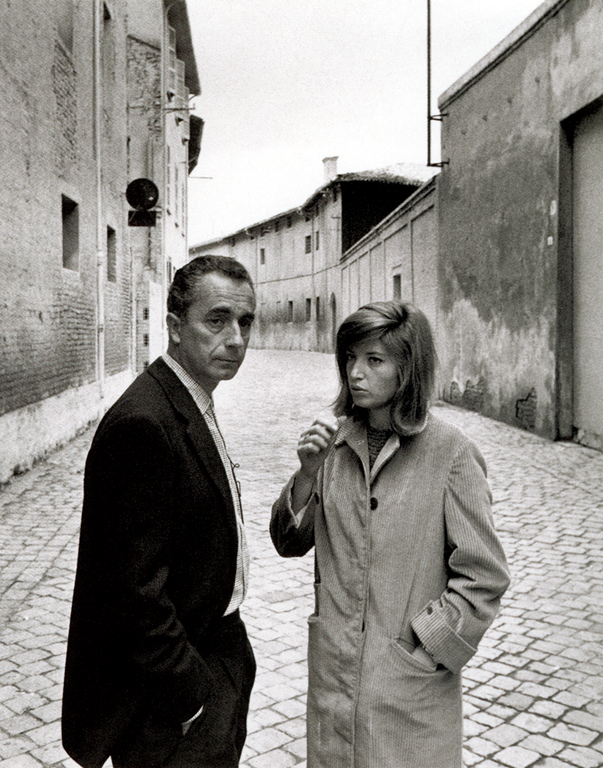

Image via Senses of Cinema.

These are themes that Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni subtly explores in his films. As of this writing, I have seen five of his films—his “triology” (‘L'Avventura’, ‘La Notte ‘, and ‘L'Eclisse’), ‘Red Desert’, and the English-language ‘Blow-Up.’ These works span from 1960 through 1966. The first three are in black and white, with the latter two exploring color.

As Martin Scorsese and others have eloquently explained in interviews and the former’s ‘My Voyage to Italy’ documentary, postwar Italian cinema—neorealism—explored the poverty and everyday struggles of Italy following the collapse of fascism and the second World War. Then, Rossellini and others began exploring a more Hollywood melodrama (per Scorsese) style. Italy, at this time, was starting to improve economically, due to industry, the Marshall Plan, and the general wave of western Europe’s rebirth following the war.

Monica Vitti in ‘L'Avventura’. She appeared in four of these five films. Image via Film Forum.

As of 1960, particularly in Northern Italy and the fashion capital Milan, the country had propelled to level of 20th century material wealth. ‘L’Avventura’ finds wealthy friends on a boating vacation, without much conviction for anything other than enjoyment. ‘La Notte’ finds an intellectual couple, a man who cannot surpass his playboy ways and a woman who is a searching for meaning among the skyscrapers and cocktail parties of Milan, struggling to sustain their connection. ‘L'Eclisse’ observes, through an impartial camera, the hedonistic priorities of young professionals in Rome and finance culture. ‘Red Desert’ shows a character’s unstable mental foundation amidst the industrial development of the North. ‘Blow-Up’ takes place in London, where a fashion photographer witnesses a dramatic moment that fizzes out into the cultural priorities of the moment.

‘Blow-Up’. Image via BFI.

It’s not that Antonioni does not notice inequality and other moral dilemmas of the times—it’s that the characters do not seem to much notice them. Save for ‘Blow-Up’, where, we get the sense, through the main character’s early photojournalistic exploration of a shelter as well as his motivation to solve the film’s central mystery, that there is hope—albeit it is quite an uphill journey with plenty of distractions for Thomas, the photographer.

It is said that Antonioni’s later English films are more optimistic (he says that ‘Blow-Up’ is, in a later 1960s interview available through the Criterion Collection), but the five films I observe seem to rely on the character rising to the moral occasion. And for the most part, they do not.

I do not think that Antonioni inherently dislikes modernity or prosperity—I think he observes that these things, left unchecked, can lead to atomization and the breakdown of interpersonal bonds. Particularly in Italy, a country with a rich and institutional religious heritage, modernity has removed the old bonds and has left no replacement.

Image via Pinterest.

Antonioni is responding to the flurry of economic advancement, and, maybe, in time, these characters will find answers to the questions their new surroundings have created.

I was initially drawn to this filmmaker’s work because of his cinematography and shooting style. His long takes and strong frames remind me of Stanley Kubrick and Paul Thomas Anderson. Through watching the films, and being curious by their unique approach to plot, I began to explore his sensibilities. His cinematic style is very much tied to his thematic tones—the camera is us, quietly observing. His technique and screenplays all combine to form Antonioni’s bold, distinct, artistic voice.

As Jack Nicholson aptly stated when presenting Antonioni with a lifetime achievement Oscar,

“Most movies celebrate the ways we connect with one another. The films of this master mourn the failures to connect. In the empty, silent spaces of the world, he has found metaphors that illuminate the silent places of our hearts. And found in them too a strange and terrible beauty—austere, elegant, enigmatic, and haunting.”

- JG

A closing shot from ‘La Notte.’ Image via MUBI.

See also -